THE US EMBASSY IN DUBLIN, IRELAND

INTRICATE CAST- FORMING CONCRETE ELEMENTS

By 1994 I had moved on to nonclassical designs, but due to my earlier reputation as a classicist I was commissioned by the Foreign Building program of the U.S. State Department to design its embassy in Dublin. An inoffensive, “diplomatic,” neo-Renaissance building was called for and so I created and example of the traditional rotunda building with arcaded exterior. Practically, it proved a good solution for its awkward, wedge-shaped site at an intricate intersection of streets, where it offered a continuous facade to all possible approaches. Structurally, the building utilized the latest method of cast-forming intricate concrete elements. known as the “Schokbeton” method. It was, after Eero Saarinen’s U.S. Embassy in London, the second precast structural facade. Privacy, required of all embassy buildings, is provided by a 30-foot flower-planted moat, across which two bridges gain entrance to the rotunda reception area. Offices are entered from circular galleries overlooking the reception area in the rotunda, and are reached at each level by concrete elevator and stair towers. The embassy building was the result of exhaustive study on my part. The final version was accepted as an effective solution to difficult program and site problems, a mannerist, monumental, yet lively building, symbolizing government. - John M Johansen

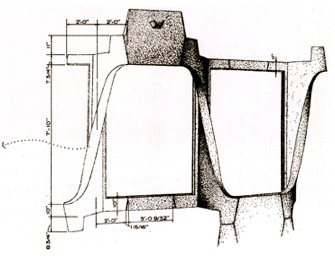

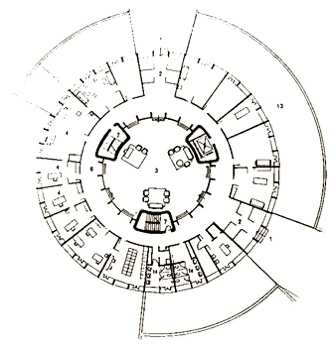

Images right, top to bottom: early study of octagonal idea; ariel view of plan; interior rotunda showing three-story structural arcade; Johansen’s drawing of precast concrete unit showing attachment to ring beams.

Website Copyright © 2011 John M Johansen All Rights Reserved

No information, photos, videos or audio on this website may be distributed, copied

or otherwise used without the written permission of John M Johansen or his representative

Website created by John Veltri and Marguerite Lorimer EarthAlive Communications www.earthalive.com

Please direct inquires to info@earthalive.com

The American Embassy in Dublin, Ireland, built in 1964, required exhaustive research and study. Its five-story cylindrical shape, on a 110-ft. diameter, presents, according to Johansen, "a façade that turns its back on no one."

Set on a rusticated granite base, the 30-foot flower-planted moat provides essential privacy; the only way to access the building is over one of two bridges. Johansen also made studies of how soot streaks the concrete so that the walls would weather with character. Made of concrete precast in Holland, the basic structural element is a twisted I, which, multiplied and dovetailed together, turns window frames into walls.

The biggest queues in New York this summer were at the Metropolitan Museum, where crowds flocked to see the clothes Jacqueline Kennedy wore during her White House years. Throughout those years the hands of the “Doomsday Clock”, the era’s symbol of nuclear peril, stood further from the midnight of Armageddon than at any other time during the Cold War. Americans never had it so good, or felt so at home in the world.

Forty years on, if you had to chose a single building to sum up that period in modern American history, one of the leading contenders would be found, not in the United States, but thousands of miles away on the other side of the Atlantic. John M Johansen’s US Embassy in Dublin was one of the most controversial buildings of the time but has come to symbolise the golden age of American architecture.

The embassy’s triangular site, comprising two large, redbrick dwellings and their tree-lined gardens at the intersection of Elgin and Pembroke Roads in Ballsbridge, was purchased in 1955 to replace the old diplomatic mission on Merrion Square.

In the 1950s, openness was both a top design priority and a US diplomatic objective, according to Jane C Loeffler, author of The Architecture of Diplomacy: Building America’s Embassies. Embassy designs were to be “friendly” and “inviting” American buildings that also reflected the “foreignness” of faraway places. Not until the mid-1960s did embassy priorities shift towards increasing security in the face of a changing and more threatening world.

Johansen’s embassy is a small building but a visually dynamic one. A mannerist rotunda with an arcaded exterior, it is more void than solid, a sort of deconstructed Martello tower or hollowed-out ring fort. Originally set off against a dynamic plaza dotted with trees and granite seats, it was for many years without railings or other visible barriers. Privacy, required of all embassy buildings, was provided by a 30-foot flower-planted moat, across which two bridges gained entrance to the rotunda reception area.

Johansen, then a 40-year-old professor of architecture at Yale and the son-in-law of Walter Gropius - who founded the Bauhaus at Dessau - was retained in November 1956 to design the embassy. Until then he had designed only houses. He was selected, he believes, because he was in his “neoclassic phase at the time.”

The design did not come easily. His first scheme, of May 1957, was a four-storey, skeleton frame and glass structure, based on a square plan with an open interior court. The State Department’s Foreign Building Office felt it “would create a heavy scale effect” and asked for revisions. Of the revised scheme, they thought that “the details of the façade still left much to be desired.” In remarks that were later struck from the record, the FBO’s Director even accused Johansen of copying the design “from the modernistic bus terminal” – Busarus – recently completed by Michael Scott.

In an unusual move, Johansen was asked to “shelve the entire plan and design” and prepare a new one. This two-story octagonal scheme, with projecting balconies and vertical fins on the exterior, fared little better and was followed by a three-storey version, which was considered “poetic but confused.”

Johansen liked his octagonal design. “I thought it was quite a lovely building. You get so close to a thing, you don’t want to let go of it. I held onto it for so long, I almost struck out.” He was within a hair’s breadth of losing the commission in early 1958. “In the midst of my confusion, Eero Saarinen, who designed the US Embassy in London, put his arm around me like an older brother, and said, ‘You think this is the best building you’re ever going to do. You think this is the big commission. It’s not.’ I thought it was so huge and so important, it stood in the way of my creative process.”

In May, inspired by ring-forts and Martello towers, he finally came up with a cylindrical scheme. The shape made sense of the triangular site. “It took me a long time to move into the circle, which turns its back on nobody,” he recalls.

Camelot’s spell still enthralls

The Sunday Times © Shane O’Toole September 2, 2001

The project soon became a political football. In a power struggle that was only marginally related to architecture, Ohio Democrat Wayne Hays, chairman of a powerful House Committee, directed his wrath against John Johansen’s Dublin design, which he likened to “a modernistic mausoleum”. Someone else compared it to “a series of flapjacks with a pat of butter on top.” Without Hays’s approval, the State Department could not build new embassies.

Until John F Kennedy moved into the White House early in 1961, nothing happened to resolve the controversy. By coincidence, Johansen knew the president from his school days at Choate in Connecticut and later at Harvard. Ireland was now high on the presidential agenda in any event. In September 1961, Kennedy wrote to Hays: “While I agree that the design will not please all tastes, the delay and expense involved in redesigning the building indicates that we should go ahead with the present design.” Hays conceded. In his terms, he had won the battle. The president of the United States was forced to acknowledge his singular importance by personally asking him to relent in his objections and to allow the project to proceed.

Johansen’s collaborator during construction was Michael Scott. Work got underway in 1962 and the embassy was completed in May 1964. The finished result was enthusiastically received at home and abroad. In Washington, a State Department official declared, “The cornerstone of our policy is to have the best architects produce the best buildings.”

The Dublin Embassy has two service storeys below ground and three storeys above. The diameter of the building is 100 feet. The rotunda is 50 feet high and 50 feet across. Used as both a reception area and entertainment space, it is ringed with an ambulatory of open corridors, with wedge-shaped offices lining the perimeter.

Structurally, the building made use of the latest method of cast-forming intricate concrete elements, a Dutch system known as the Schokbeton method. Two circular, arcaded facades of reconstructed limestone support precast concrete floors. No columns are needed. Johansen went to Holland to approve the castings, which were transported by barge to Dublin port. “When they put up the outside ring at the ground floor it was perfect, with separations between the units of one-quarter-inch all the way round,” he recalls.

The vertical supports twist at angles of 90 degrees, enclosing large flat panes of fixed glass, alternated with French doors that give onto balconies. “Little scuppers drain the balconies,” says Johansen. “At that time a modern architect would only do something decorative if it derived from a function or structural detail. It was dishonourable otherwise.”

The overall effect was of lightness - aran-knit, medieval tracery, a filigree piece of stone jewellery. It is now encased behind steel bollards, railings and ponderous entrance ramps. The world has changed and, in this respect, not for the better.

Johansen's muscular and expressive work has spanned the entire post-War period of American history. He has lived to see the ad-hoc approach and improvisation of his Mummers Theatre in Oklahoma City (1965-1970) acknowledged as a precedent for the Centre Pompidou in Paris, as well as for Frank O Gehry's juggled masses and iconic use of commonplace materials.

Described recently by prominent American architect James Wines as "an antenna of what's in the air, the changing sensitivities of the times," Johansen is now 85.A member of the American Academy of Fine Arts and Letters, like both his parents before him, he still works two days every week at his office off Union Square in Manhattan.

He still believes in the art of that which is not yet possible, but theoretically realistic. Next year, Princeton Architectural Press will publish a book of his "Nano-architecture" - projects for buildings of the future that could be programmed to "grow" using breakthroughs in molecular nanotechnology.

About Dublin, he remains philosophical: "The only thing that angers me is that the concrete in certain offices has been painted. I scolded them for that."